Hello everyone,

I wrote a piece about becoming an Antifragile Investor a few weeks ago. It stemmed from the belief of Nassim Nicholas Taleb that for living organisms, gradual exposure to stress makes us grow and protects us from future threats.

It was a concept that could be applied to doing exercises for muscle growth or investing in the stock market for portfolio growth. But what about a company? Surely a company that has been around for decades must have some antifragility seeped into its core like the deep roots of an old tree that makes it branch out wider and stronger.

Berkshire has been in business for the last 60 years. The answer to why they have survived for so long is in a 2014 Annual Shareholder Letter. Today it's known as ‘The Berkshire System.’

Charlie Munger, the vice-chairman of BH, analyses the sources of success for the Berkshire System that has allowed them to grow and become antifragile. He says:

What was Buffett aiming at as he designed the Berkshire system?

Well, over the years I diagnosed several important themes:

(1) He particularly wanted continuous maximization of the rationality, skills, and devotion of the most important people in the system, starting with himself.

(2) He wanted win/win results everywhere--in gaining loyalty by giving it, for instance.

(3) He wanted decisions that maximized long-term results, seeking these from decision-makers who usually stayed long enough in place to bear the consequences of decisions.

(4) He wanted to minimize the bad effects that would almost inevitably come from a large bureaucracy at headquarters.

(5) He wanted to personally contribute, like Professor Ben Graham, to the spread of wisdom attained.

When Buffett developed the Berkshire system, did he foresee all the benefits that followed? No. Buffett stumbled into some benefits through practice evolution. But, when he saw useful consequences, he strengthened their causes.

What interests me more is the way the big companies start having smaller teams and a more decentralized approach to management.

At the Omaha yearly meeting of BH, a question came up what kind of organizational structure exists in Berkshire? Charlie had this to say:

There are two main reasons Berkshire has succeeded. One is its decentralization. Decentralization almost to the point of abdication. There are only 28 people at headquarters in Omaha.

This reminded me of another organizational obsessor called Steve Jobs. As Apple continued to bleed money in the late 1980s and early 1990s, they bought the company NEXT founded by Steve. When he returned to Apple, he fired most of the general managers. The Harvard Business Review gave a good analysis of why:

When Jobs arrived back at Apple, it had a conventional structure for a company of its size and scope. It was divided into business units, each with its own P&L responsibilities. General managers ran the Macintosh products group, the information appliances division, and the server products division, among others. As is often the case with decentralized business units, managers were inclined to fight with one another, over transfer prices in particular. Believing that conventional management had stifled innovation, Jobs, in his first year returning as CEO, laid off the general managers of all the business units (in a single day), put the entire company under one P&L, and combined the disparate functional departments of the business units into one functional organization.

However, this trend is also present in the meeting culture of today’s workplace. The company stands still to discuss a topic for 45 minutes in a room on a solution that can be solved with 10 minutes of critical thinking done before the meeting starts. Again, this is something addressed by the conglomerate Amazon where Jeff Bezos insists on a memo-writing-based tactic.

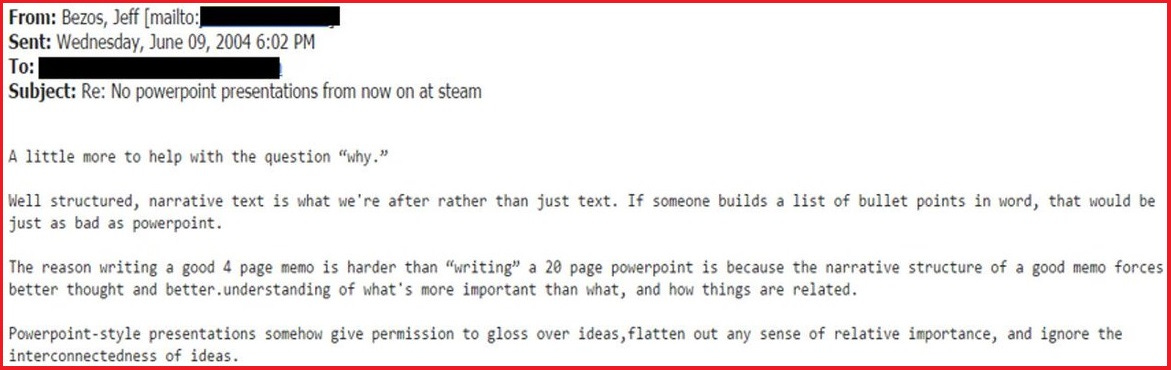

On the eve of 2004, the Amazon founder sent this email to the entire company:

In the now-famous email, he banned the use of PowerPoint for what is called a ‘six-page memo’ method. He argued that:

This would make the leaders of the company more prepared before a meeting

They would have a better solution with a unique idea and a better strategy

Much shorter sessions to save time

Now consider the idea of trust. All of Amazon, Apple, and Berkshire and their management style have these two traits in common:

Small Teams is what Amazon has believed in from Day 1. In the dot-com era, the need for the speed of decisions to be made is forever desired, even needed to survive the completion of these new companies. High performance, according to Tom Godden of AWS Enterprise Strategist.

To truly become a high-performing agile organization, you must look at your organization structure differently and be willing to change your mindset and behavior.

Deep Expertise is needed in a decentralized organization. It is necessary as an organization that is built of small teams on the back of trust, needs to be experts in their respective fields. The hiring process of Amazon and Apple was similar, Walter Isaacson says:

It’s never been easy to work at Amazon. When Bezos interviews people, he tells them, “You can work long, hard, or smart. But at Amazon.com you can’t choose two of the three.” Bezos makes no apologies.

This reminds me a lot of the way Steve Jobs operated. Sometimes such a style can be crushing, and to some people it may feel tough or even cruel. But it also can lead to the creation of grand, new innovations and companies that change the way we live.

There is significant compounding power in hiring the right people, especially when the company is small or wants to increase its market share at scale while maintaining breakeven costs in the first few years of the business.

But it is not just for companies, but also for the people like us, who want to grow exponentially (compounding) instead of gradually (linear). That’s again where the universality of Antifargaility comes into play again. To become an antifragile conglomerate like Amazon and Berkshire or even an antifragile person like Jeff and Charlie Munger, the playbook is the same as The Berkshire System.

To end, I found an awesome insight into ‘The Berkshire System” by Fredrick Gieschen’s Neckar Substack which said:

To me, this reads like a how-to for designing one’s life:

(1) Maximize your impact by developing your unique skills, acting rationally, and empowering others.

(2) Seek win/win relationships and be a good partner.

(3) Think and act long-term to compound positive effects. Carefully consider and align incentives.

(4) Be wary of the inevitable complacency, corrosion, and corruption. Design your life to minimize these forces.

(5) Enrich the world by sharing what you learn.

Big corporations follow the above blueprint for each of their members of small teams which makes them antifragile and in the end, grow.